10 KiB

Vector math

Introduction

This tutorial is a short and practical introduction to linear algebra as

it applies to game development. Linear algebra is the study of vectors and

their uses. Vectors have many applications in both 2D and 3D development

and Pandemonium uses them extensively. Developing a good understanding of vector

math is essential to becoming a strong game developer.

Note:

This tutorial is **not** a formal textbook on linear algebra. We

will only be looking at how it is applied to game development.

For a broader look at the mathematics,

see https://www.khanacademy.org/math/linear-algebra

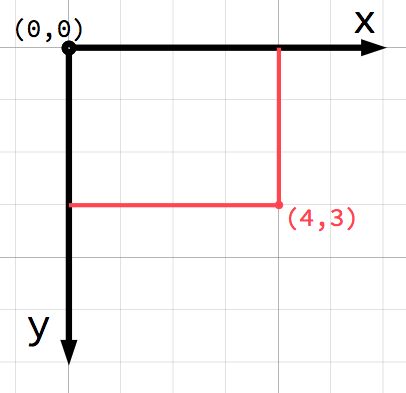

Coordinate systems (2D)

In 2D space, coordinates are defined using a horizontal axis (x) and

a vertical axis (y). A particular position in 2D space is written

as a pair of values such as (4, 3).

Note:

If you're new to computer graphics, it might seem odd that the

positive y axis points downwards instead of upwards,

as you probably learned in math class. However, this is common

in most computer graphics applications.

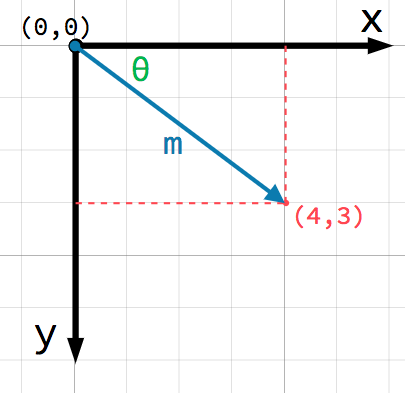

Any position in the 2D plane can be identified by a pair of numbers in this

way. However, we can also think of the position (4, 3) as an offset

from the (0, 0) point, or origin. Draw an arrow pointing from

the origin to the point:

This is a vector. A vector represents a lot of useful information. As

well as telling us that the point is at (4, 3), we can also think of

it as an angle θ and a length (or magnitude) m. In this case, the

arrow is a position vector - it denotes a position in space, relative

to the origin.

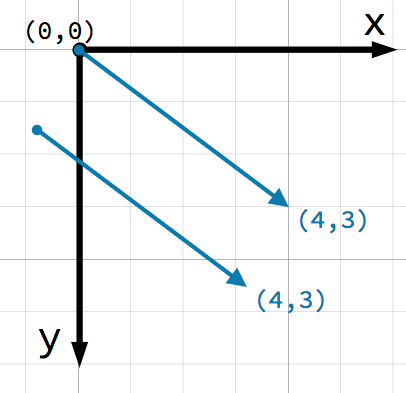

A very important point to consider about vectors is that they only represent relative direction and magnitude. There is no concept of a vector's position. The following two vectors are identical:

Both vectors represent a point 4 units to the right and 3 units below some starting point. It does not matter where on the plane you draw the vector, it always represents a relative direction and magnitude.

Vector operations

You can use either method (x and y coordinates or angle and magnitude) to

refer to a vector, but for convenience, programmers typically use the

coordinate notation. For example, in Pandemonium, the origin is the top-left

corner of the screen, so to place a 2D node named `Node2D` 400 pixels to the right and

300 pixels down, use the following code:

gdscript GDScript

```

$Node2D.position = Vector2(400, 300)

```

Pandemonium supports both `Vector2` and

`Vector3` for 2D and 3D usage, respectively. The same

mathematical rules discussed in this article apply to both types.

Member access

-------------

The individual components of the vector can be accessed directly by name.

gdscript GDScript

```

# create a vector with coordinates (2, 5)

var a = Vector2(2, 5)

# create a vector and assign x and y manually

var b = Vector2()

b.x = 3

b.y = 1

```

Adding vectors

--------------

When adding or subtracting two vectors, the corresponding components are added:

gdscript GDScript

```

var c = a + b # (2, 5) + (3, 1) = (5, 6)

```

We can also see this visually by adding the second vector at the end of

the first:

Note that adding `a + b` gives the same result as `b + a`.

Scalar multiplication

---------------------

Note:

Vectors represent both direction and magnitude. A value

representing only magnitude is called a **scalar**.

A vector can be multiplied by a **scalar**:

gdscript GDScript

```

var c = a * 2 # (2, 5) * 2 = (4, 10)

var d = b / 3 # (3, 6) / 3 = (1, 2)

```

Note:

Multiplying a vector by a scalar does not change its direction,

only its magnitude. This is how you **scale** a vector.

Practical applications

Let's look at two common uses for vector addition and subtraction.

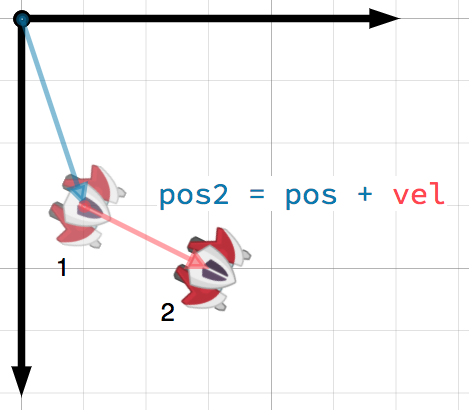

Movement

A vector can represent any quantity with a magnitude and direction. Typical examples are: position, velocity, acceleration, and force. In

this image, the spaceship at step 1 has a position vector of (1,3) and

a velocity vector of (2,1). The velocity vector represents how far the

ship moves each step. We can find the position for step 2 by adding

the velocity to the current position.

Tip: Velocity measures the change in position per unit of time. The new position is found by adding velocity to the previous position.

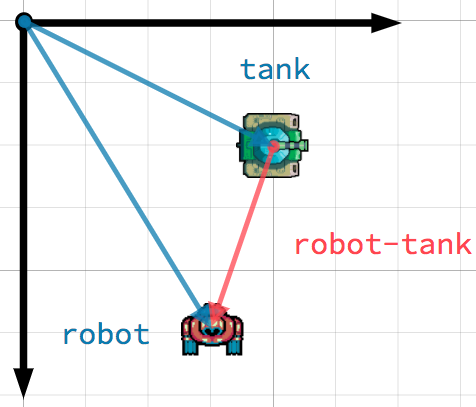

Pointing toward a target

In this scenario, you have a tank that wishes to point its turret at a robot. Subtracting the tank's position from the robot's position gives the vector pointing from the tank to the robot.

Tip:

To find a vector pointing from A to B use B - A.

Unit vectors

A vector with **magnitude** of `1` is called a **unit vector**. They are

also sometimes referred to as **direction vectors** or **normals**. Unit

vectors are helpful when you need to keep track of a direction.

Normalization

-------------

**Normalizing** a vector means reducing its length to `1` while

preserving its direction. This is done by dividing each of its components

by its magnitude. Because this is such a common operation,

`Vector2` and `Vector3` provide a method for normalizing:

gdscript GDScript

```

a = a.normalized()

```

Warning:

Because normalization involves dividing by the vector's length,

you cannot normalize a vector of length `0`. Attempting to

do so will result in an error.

Reflection

----------

A common use of unit vectors is to indicate **normals**. Normal

vectors are unit vectors aligned perpendicularly to a surface, defining

its direction. They are commonly used for lighting, collisions, and other

operations involving surfaces.

For example, imagine we have a moving ball that we want to bounce off a

wall or other object:

The surface normal has a value of `(0, -1)` because this is a horizontal

surface. When the ball collides, we take its remaining motion (the amount

left over when it hits the surface) and reflect it using the normal. In

Pandemonium, the `Vector2` class has a `bounce()` method

to handle this. Here is a GDScript example of the diagram above using a

`KinematicBody2D`:

gdscript GDScript

```

# object "collision" contains information about the collision

var collision = move_and_collide(velocity * delta)

if collision:

var reflect = collision.remainder.bounce(collision.normal)

velocity = velocity.bounce(collision.normal)

move_and_collide(reflect)

```

Dot product

~~~~~~~~~~~

The **dot product** is one of the most important concepts in vector math,

but is often misunderstood. Dot product is an operation on two vectors that

returns a **scalar**. Unlike a vector, which contains both magnitude and

direction, a scalar value has only magnitude.

The formula for dot product takes two common forms:

and

However, in most cases it is easiest to use the built-in method. Note that

the order of the two vectors does not matter:

gdscript GDScript

```

var c = a.dot(b)

var d = b.dot(a) # These are equivalent.

```

The dot product is most useful when used with unit vectors, making the

first formula reduce to just `cosθ`. This means we can use the dot

product to tell us something about the angle between two vectors:

When using unit vectors, the result will always be between `-1` (180°)

and `1` (0°).

Facing

------

We can use this fact to detect whether an object is facing toward another

object. In the diagram below, the player `P` is trying to avoid the

zombies `A` and `B`. Assuming a zombie's field of view is **180°**, can they see the player?

The green arrows `fA` and `fB` are **unit vectors** representing the

zombies' facing directions and the blue semicircle represents its field of

view. For zombie `A`, we find the direction vector `AP` pointing to

the player using `P - A` and normalize it, however, Pandemonium has a helper

method to do this called `direction_to`. If the angle between this

vector and the facing vector is less than 90°, then the zombie can see

the player.

In code it would look like this:

gdscript GDScript

```

var AP = A.direction_to(P)

if AP.dot(fA) > 0:

print("A sees P!")

```

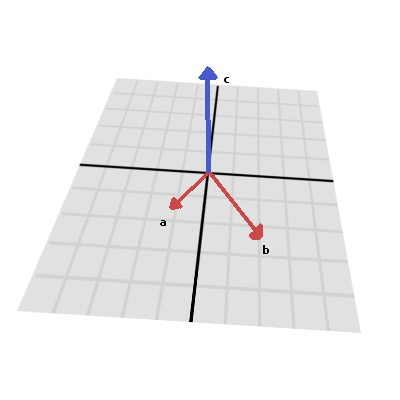

Cross product

Like the dot product, the cross product is an operation on two vectors. However, the result of the cross product is a vector with a direction that is perpendicular to both. Its magnitude depends on their relative angle. If two vectors are parallel, the result of their cross product will be a null vector.

The cross product is calculated like this:

gdscript GDScript

var c = Vector3()

c.x = (a.y * b.z) - (a.z * b.y)

c.y = (a.z * b.x) - (a.x * b.z)

c.z = (a.x * b.y) - (a.y * b.x)

With Pandemonium, you can use the built-in method:

gdscript GDScript

var c = a.cross(b)

Note:

In the cross product, order matters. a.cross(b) does not

give the same result as b.cross(a). The resulting vectors

point in opposite directions.

Calculating normals

One common use of cross products is to find the surface normal of a plane

or surface in 3D space. If we have the triangle ABC we can use vector

subtraction to find two edges AB and AC. Using the cross product,

AB x AC produces a vector perpendicular to both: the surface normal.

Here is a function to calculate a triangle's normal:

gdscript GDScript

func get_triangle_normal(a, b, c):

# find the surface normal given 3 vertices

var side1 = b - a

var side2 = c - a

var normal = side1.cross(side2)

return normal

Pointing to a target

In the dot product section above, we saw how it could be used to find the angle between two vectors. However, in 3D, this is not enough information. We also need to know what axis to rotate around. We can find that by calculating the cross product of the current facing direction and the target direction. The resulting perpendicular vector is the axis of rotation.

More information

For more information on using vector math in Pandemonium, see the following articles:

- `doc_vectors_advanced`

- `doc_matrices_and_transforms`